skin in the game

Cap management is one of the biggest decisions you’ll get to make as a Not Yet Named member. How we mix the skins and juice during fermentation - how hard, how often, how long and with what technique - can completely change the wine’s style. Every permutation leads somewhere different on a scale from light and perfumed to bold and powerful.

what happens

When grapes ferment, the juice and the skins naturally separate. The juice sinks to the bottom of the tank while the skins and seeds catch a ride via the CO2 byproduct of fermentation and float to the top, forming what we call “the cap.” If we left that cap floating there untouched, we’d be left with a rather flavourless pale wine, with more than a splash of vinegar and some other unpalatable faults.

So we need to mix the grape juice with the skins to pull out colour, flavour, and tannin and keep the wine healthy. This is done by gently pushing the skins down (punchdowns) or by pumping juice over the top (pumpovers), and there’s a few other emerging techniques that sit on the scale dominated by these two options.

mix it up

When red must is fermenting in contact with skins, the carbon dioxide that is produced rises to the top and takes the skins with it, resulting in a layer of skins separated from the juice on the top.

This can be problematic for a few reasons;

If the skins stay dry for a long period of time, acetic acid bacteria can thrive in contact with air and turn the wine into vinegar. The exposed surface allows oxygen and bacteria to interact with residual sugars and ethanol. One specific type of bacteria, Acetobacter, converts alcohol into acetic acid, creating vinegar-like aromas.

Another product of fermentation is heat. On the one hand heat helps to increase the rate of the alcoholic fermentation but it can also completely kill the ferment if it reaches c. 35c. The heat builds up particularly just below the cap of skins as the heat rises but cannot escape.

The cap also prevents oxygen from getting into the juice and a little bit is essential to enable yeasts to multiply and keep the fermentation going.

But above all, the skins being in contact with juice allows the wine to macerate. This maceration is responsible for all of the specific characteristics of sight, smell and taste that differentiate red wines from white wines. Phenolic compounds (anthocyanins and tannins) are primarily extracted, participating in the colour and overall structure of wine.

With a few quirky exceptions (teinturier grapes, which have red flesh as well as skins), almost all red grapes actually have clear juice. If you crushed a bunch of our Nebbiolo and pressed it straight away, you’d end up with something that looks like white wine. The deeper colour, the tannins that give structure, and much of the flavour all live in the skins, not so much in the juice.

Aromas and aroma precursors, nitrogen compounds, polysaccharides (in particular, pectins) and minerals are also liberated in the must or wine during maceration. This maceration, aka extraction, is accentuated by the amount of punching as well as temperature, time and level of alcohol. So, yeah, it’s pretty important for reds!

punchdowns

“Three things about punchdowns;

• Gentle extraction of colour and tannin.

• Preserves floral aromatics and finesse.

• Creates more delicate, approachable wines, but limited tannin and structure.”

Punchdowns are the gentle, hands-on approach to extraction. It’s the traditional method of climbing onto the top of the tank and literally pushing the floating skins back into the juice with a paddle, a stick or traditionally hands and feet. It’s slower, more manual, and less dramatic than other methods, but it has a delicate impact on the style of wine produced, preventing all the problems listed above whilst only extracting a little from the skins.

By submerging the cap (like a submerged cap, see below, but not permanent) rather than breaking it apart, punchdowns extract tannin and colour more slowly and carefully. This means the final wine often has a softer texture, more perfumed aromatics, and a lighter colour.

But there’s a trade-off. Punchdowns, if used exclusively, can sometimes result in wines that feel a bit too light, lacking in mid-palate weight or long-term ageability. That’s why some winemakers only use punchdowns when they want a particularly elegant expression - something you can drink sooner, rather than needing years of patience in the cellar.

pumpovers

Pumpovers, also known as remontage, take a very different approach. Instead of gently pushing skins down, we pump juice up from the bottom of the tank and spray it back over the cap. This soaks and breaks up the skins, extracts tannins more effectively, and introduces a controlled amount of air at the same time. It’s a more vigorous method, and it leaves a bigger imprint on the wine’s style.

That oxygen element of the introduction of air can be very important, if a wine is showing signs of reduction, the introduction of some oxygen can be beneficial (it may not have an effect if the cause of the reduction, aromas produced by stressed yeast, is something else) to fixing it up. When the rotten egg of reduction is laid at your tank, some people take the pumpover a step futher with a ‘rack and return’ or delestage. This drains all the liquid out of the thank before returning over the top, making sure that maximum. Reduction in ferment however is another topic that undoubtedly deserves its own blog.

With pumpovers, you get more colour, more body, and firmer tannins. Oxygen also helps stabilise colour, which is particularly useful for Nebbiolo since its pigments are naturally unstable. This means pumpovers can produce wines with deeper hues and longer-lasting structural integrity. It’s a method favoured by winemakers aiming for a bolder, ageworthy style of wine.

“Three things about pumpovers

• Stronger extraction of colour and tannin.

• Introduces oxygen, helping stabilise colour.

• Builds body and ageing potential, but risks harsher tannins.”

But again, there’s a balancing act. Too many pumpovers, or too aggressive a schedule, and tannins can become harsh, drying, and angular. Oxygen, if over-applied, can also dull Nebbiolo’s delicate aromatics. So while pumpovers are a powerful tool, they require restraint and timing. Choosing a pumpover-heavy approach for us would be doubling down on structure and longevity but risking a loss of aromatics.

Some other techniques

For our third vintage in California, we were fortunate to have access to an innovative technique known as ‘Pulsair’ which saved a lot a of time for us and enabled something closer to punchdowns but on a larger scale.

A submerged cap is a technique used during fermentation where the cap is kept submerged under the surface of the liquid by fixing a physical barrier, such as a wooden grid or stainless steel plate, over the cap to hold it down. For our bonus edition of Cabernet Franc with Darcie Kent in Livermore, California, friend of Not Yet Named Dayton Charles put this to the test having used it to great effect in the Swartland, South Africa.

The Schedule: How Often, how long, How Hard?

The real magic lies not just in choosing punchdowns or pumpovers, but in how often we do them, how forcefully, and at what stage of fermentation. Early on, during the first few days, extraction is mostly about colour. Later, as alcohol levels rise, tannins extract more readily and that’s where overdoing it can lead to bitterness. So the schedule of mixing is a fine-tuned dial that sets the final balance.

A gentle schedule might involve one or two light punchdowns per day. This keeps the cap wet, avoiding faults, and gently pulls out colour and tannin. A powerful schedule, meanwhile, might involve two or three pumpovers per day, sometimes with additional punchdowns. This is the road to darker, more tannic wines that demand bottle age before drinking. For those who have had the experience of a Rodica Refosk, sleep is sacrificed to punchdown the cap every 4 hours irrespective of the time of the night! A balanced schedule could also mix things up - one or two punchdowns, plus a light pumpover if a little oxygen would help the ferment. This approach often gives the best of both worlds, extracting enough structure without overpowering the aromatics.

Impact on Taste

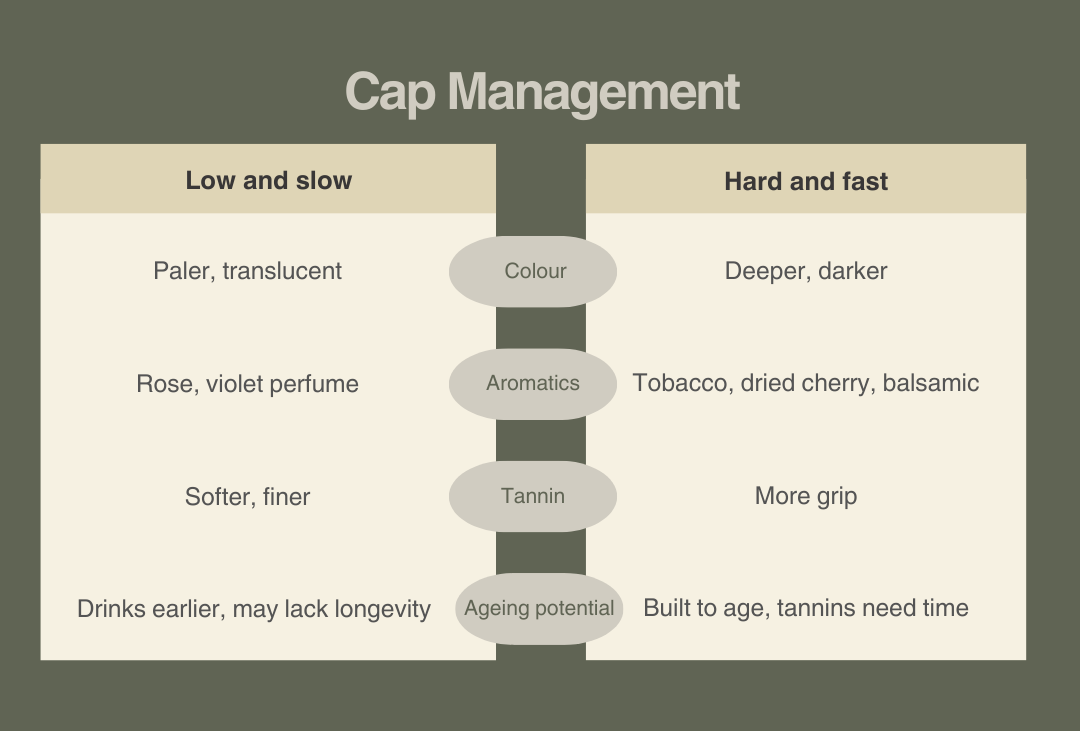

This decision is not just about fermentation technique - it’s about flavour, texture, and the kind of wine you want to drink in a few years’ time. A gentle approach gives us lighter colour, silkier tannins, and more delicate aromatics. These wines are seductive and ready to drink sooner, but they may not have the backbone to last decades. A powerful approach creates wines of density, tannic grip, and serious ageing potential - but these wines may need years to loosen up and soften the edges.