A crush on grapes

step 1

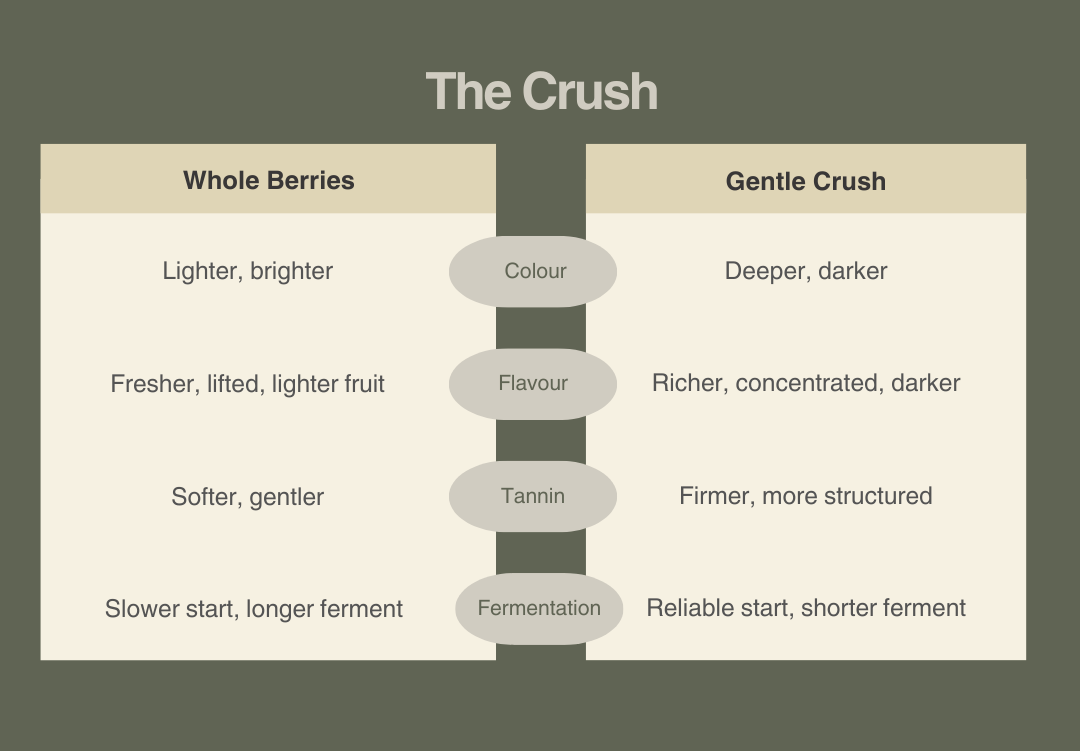

Once grapes are harvested and brought into the winery, one of the first big decisions is what to do after destemming, if you decide to do that at all. Writing this from Piedmont and with two Nebbiolos in the offing, we are skipping what would be a very controversial decision to use whole bunch and following the most prevalent method of destemming. Instead our vote will centre whether we crush the berries prior to fermentation, or leave them whole. Let’s break down the exocarp of this topic.

why bother at all

Suppose our grapes have been lovingly hand harvested. On the steep steps of Roddi in Northern Barolo, a small band of young and others not-so–young winemakers break their backs, traipsing betwen rows in a crab-like half crawl, half crouch positions just to limit the damage caused to the berries when picking. And then we might go and crush them.

Crushing breaks open the skins, releasing juice and exposing pulp, sugars, and nutrients exposing them to yeasts on the berries and in the general environment. With crushed fruit, extraction of colour and tannins begins right away, the must becomes a more even mix, and yield can increase (in a very minor way) because more juice is made available from the start. For big, structured reds, this is often the most reliable way to go. The result is a wine that’s deeper in colour, richer in texture, and more concentrated in flavour. Aromatics become more intense and pronounced, the fruit profile darkens, and tannins firm up, giving structure and backbone.

Crucially in some cases, it also starts the ferment quicker. A fast fermentation isn’t just about speed - it’s about avoiding spoilage and practicality. Once the Sacch. yeast gets going, it dominates the microbial population, leaving little room for unwanted wild yeasts or spoilage organisms to gain a foothold. A prompt start also frees up tank space, this could be essential if you plan to use the same fermentation tanks multiple times in harvest. If it’s the last time you’ll use the tank that harvest, you’ll probably also just want it over and done with asap, so a speedy ferment can be emotionally pleasing.

“Three reasons to crush;

• Kickstarts fermentation by giving yeast easy access to sugars.

• Promotes colour and tannin extraction.

• Ensures a well mixed must, making temperature and nutrient management easier.”

Why Some Don’t Crush

Not every winemaker wants immediate juice release for every wine. Imagine the grapes are like little flavour bombs, with whole berries they stay complete to begin with but will eventually explode. Inside each berry, mini-fermentations begin, which is the the basis of carbonic maceration (e.g. Beaujolais), which gives wines those juicy, lifted strawberry and violet notes but then causes the mini-bomb to explode. As the sugar is released gradually as each berry pops, it draws out the whole process. The result can be wines that sing with freshness: bright aromatics, lifted fruit, and a delicate mouthfeel. Tannins are softer, colour is lighter, and the wine feels airy and elegant rather than dense or concentrated. It’s a choice for wines where drinkability and subtlety is your goal or any style where aromatic lift and finesse take priority over sheer power. This makes it a tough choice for Nebbiolo which can do both…

“Three reasons not to crush;

• Encourages partial carbonic fermentation, adding fruity notes.

• Slows down fermentation, giving more delicate wines.

• Reduces tannin and colour extraction”

the tools for the job

The tools used for this step have changed over time. Back in the day, it was done by foot, with pickers stomping grapes in large wooden vats. By back in the day, I mean the last three years for me. We probably won’t be using an open top fermenter this time so I’d rather not drown which sadly makes me redunadant (yet people still call me a tool). Machines have largely taken over in most places with modern crusher-destemmers allowing a winemaker to dial in just how firmly the berries are broken. The crushing mechanism of all the machines I’ve seen is a pair rollers that can be adjuted closer together, so the crush is less violent that it may sound.

Like any choice in the cellar, crushing comes with both advantages and risks. Breaking the berries guarantees more juice and a faster start to fermentation, but it can also go too far. Over-crushing can split seeds, releasing bitter, harsh compounds that linger in the finished wine. Exposing a lot of free juice too early also increases the risk of oxidation and gives spoilage microbes a head start if hygiene isn’t impeccable. Every crusher must be kept spotless; a single layer of grime is an open invitation for faults.

Crushing it

As with all decisions, no single choice will completely transform a wine but as a general correlation, wines made from crushed fruit tend to be darker, firmer, and more structured — powerful, age-worthy styles that demostrate power. Wines made from whole berries, by contrast, lean toward aromatic lift, softness, and juiciness, often making them more immediately approachable. Somewhere in between lies a partial crush, offering both backbone and brightness.