Red wine Fermentation temperature

One of the luxuries you get from working in a high-tech cellar is the opportunity to set the temperature during fermentation, which helps manage the ferment effectively and has a subtle impact on tannin extraction and preservation of aromatics. Another strategy is to have a cold room, or a big fridge, where you leave freshly picked whole bunches overnight prior to processing as we did in South Africa, this at least gives you the best possible start if you can’t easily control it from there on, but the holy grail is control at the touch of a button.

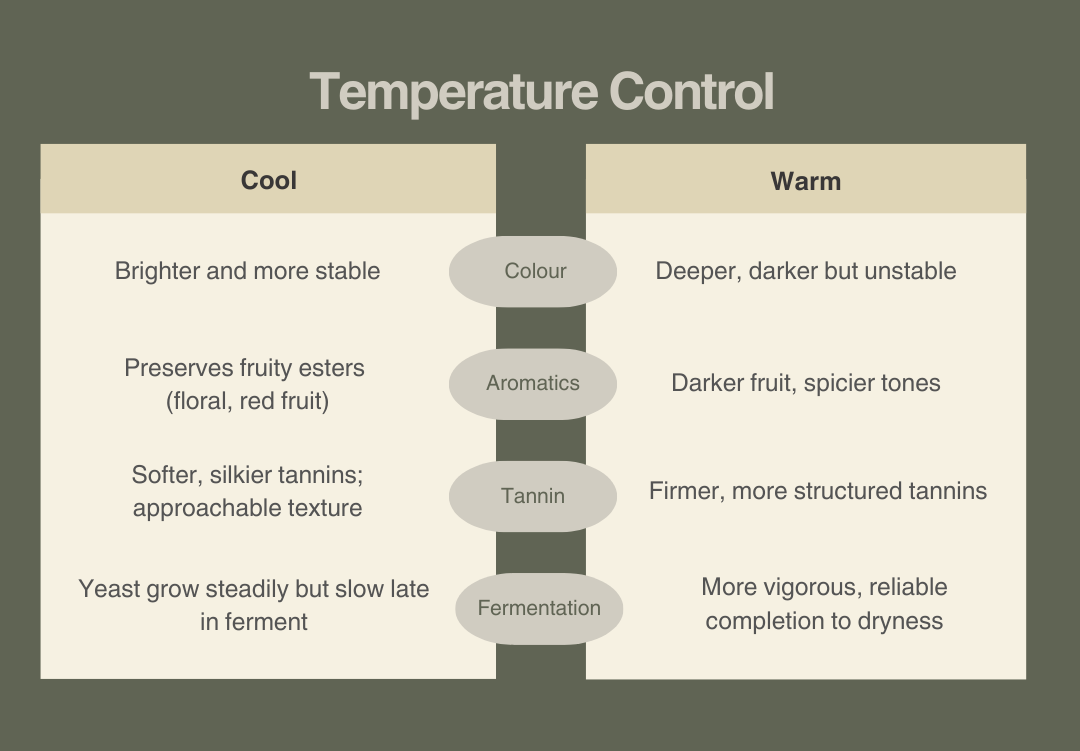

There is generally a sweet spot to choose from for your thermals. Ideally starting the fermentation (and for the first two-thirds) between 22-26°C. Once sugar depletes towards the end, we let the temperature rise naturally so the yeast can finish the job to make sure we get to dryness. Going to either end of that range, though, will give the wine a slightly different personality.

It’s a bit goldilocks

Whilst yeast multiplies in higher temperatures, they are also relatively fragile. If the temperature climbs too high, approaching 35°C, yeast cells start to struggle. Push them too far enough and they’ll simply die, leaving behind a stuck ferment and unfinished wine at the end. A kind of scorching, soggy porridge. Even before that, high heat over a sustained period of time risks burning off delicate aromas.

On the other end of the scale, if the ferment drops too cool, yeast slow down or stop altogether. The wine sits half-fermented, with little of the prized polyphenols extracted from the skins, metaphorically leaving a lot left in the tank.

Restarting a stuck ferment can be done, whether that’s caused by a ferment that’s been too hot or too cold, but it’s painful and rarely as clean as letting it run smoothly in the first place. For our current vintage in Langhe, and based on Gianluca’s experience, that sweet spot is between 22-26°C, but I’m sure that varies with grape and region.

the sweet spot

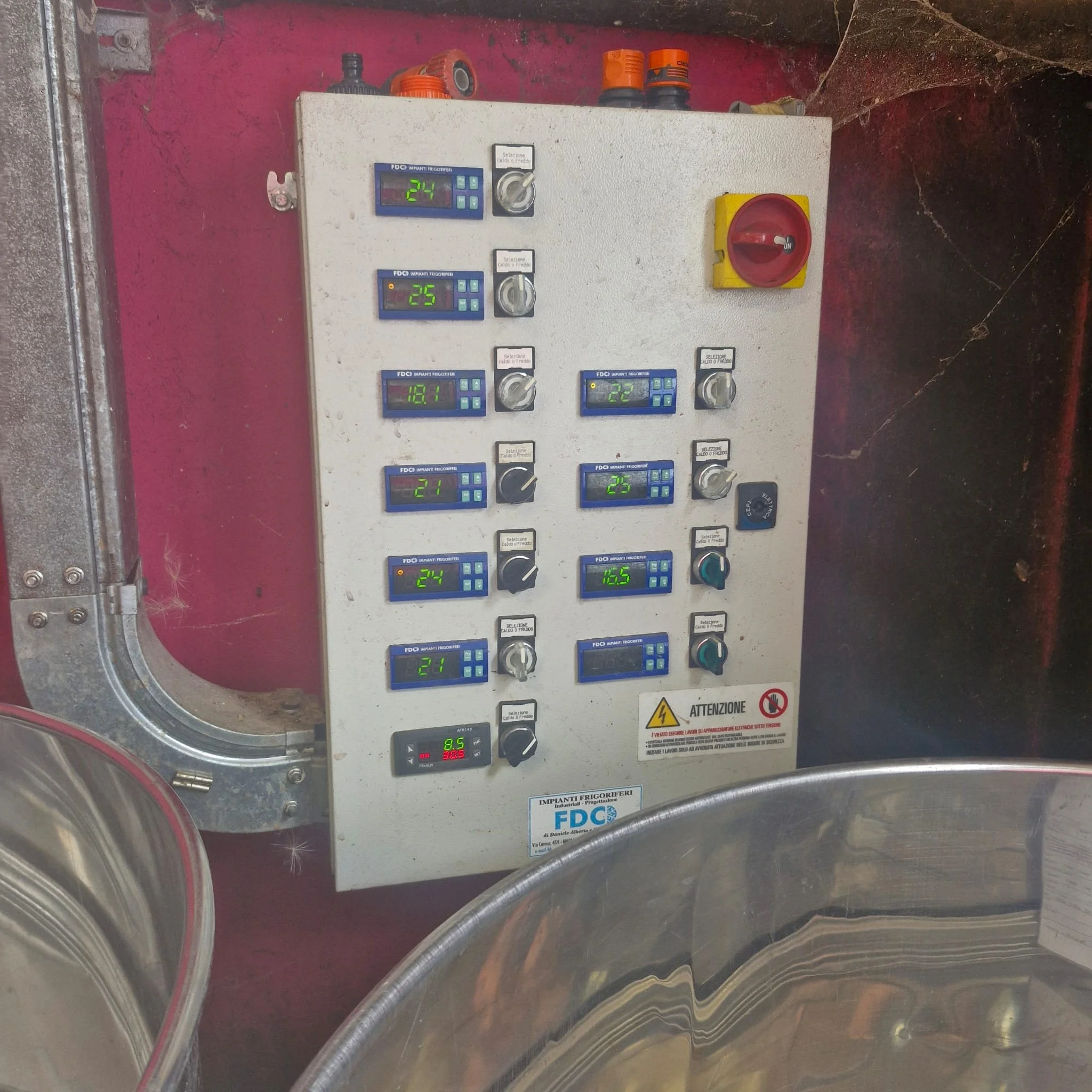

This vintage we are blessed with temperature control in our tank and can dial in exactly what we are after.

A cooler ferment means extraction happens more slowly and more gently. At 22 °C, colour compounds (anthocyanins) come out of the skins at a steadier pace and those pigments are also more stable once they’re in the wine. Delicate aroma molecules, the floral, lifted notes, are less likely to be stripped away by heat. Organoleptically your organs might notice a fresher, more aromatic wine, with brighter fruit and silkier tannins. They can feel elegant and restrained.

At 26 °C, the skins soften more quickly, so tannins and colour rush into the liquid early. The wine feels bolder straight away, deeper in colour and firmer in grip. But higher temperature is a double-edged sword: once anthocyanins are out, they’re also more prone to degradation or binding, which can mean less stable colour down the line. Here you’ll get a richer, denser wine, with more structure. They make a stronger first impression, though they may show less floral lift and freshness.

Whichever path we take, we don’t hold it there forever. Toward the end, we turn off the cooling and let the fermentation warm up naturally. This helps the yeast finish converting sugar to alcohol, ensuring the wine is properly dry, and it coaxes out the final phenols you desire.

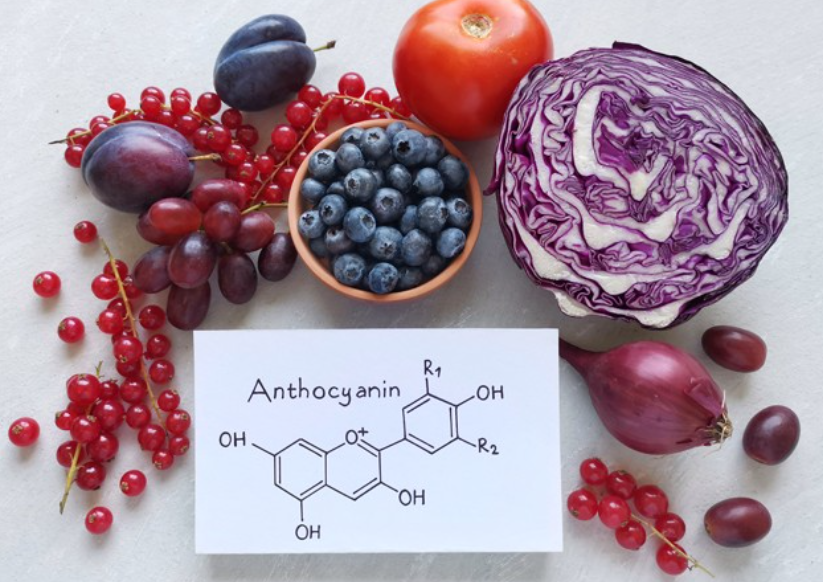

Colour

The colour doesn’t personally bother me that much but I find the science behind it fascinating, and by fascinating I really mean I don’t fully understand it but here’s my best attempt;

At cooler ferments, colour builds more slowly, so the wine may look lighter at first. Over the following months those pigments stabilise with tannins, giving a brighter, fresher ruby tone that tends to hold for years before gracefully moving toward garnet with age.

At warmer ferments around 26 °C, colour appears deep and intense early on, but those fragile pigments break down more quickly. The wine can lose brightness within months, shift to garnet sooner, and often looks more mature than a cooler-fermented wine of the same age.

Colour behaves this way because anthocyanins, the pigments in grape skins, are sensitive to heat and extraction rate. Cooler ferments release them slowly, letting them stabilise with tannins and preserve brightness.These descriptions are, of course, considering all things being equal. The total amount of tannin extracted into the wine will also promote colour stability as the molecules bind, so the condition of the grapes, punchdowns/pumpovers and maceration time will make a huge difference.

what smart people have worked out

Cool fermentations (around 15 °C) favour the formation of fruity acetate esters, while warmer fermentations (28 °C) increase the production of higher alcohols and fatty acid esters. Molina et al. (2007)

Lower fermentation temperatures slow the extraction of colour and tannin, whereas higher temperatures accelerate extraction, particularly from seeds, altering wine astringency and mouthfeel. Stoffel et al. (2021)

Reviewing a range of studies, commonly 20–25 °C (cool/moderate) vs 28–32 °C (warm/hot). Higher fermentation temperatures increase the rate of extraction of phenolics, particularly from seeds, but can also lead to greater losses of volatile aroma compounds compared with cooler ferments. Godden (2021, AWRI Technical Review)

At cooler temperatures, the reduced extraction of polyphenols alters the binding of volatile compounds, leading to fresher, more pronounced aromas; at warmer temperatures, greater phenolic extraction can suppress some aroma release. Pittari, Moio & Piombino (2021)

At 29 °C there’s a faster anthocyanin extraction with more skin softening but more degradation after. At 24 °C you get a better preservation of anthocyanins and the tannin content/structure is less affected long term (Ferrero, Lorenzo et al. 2025)

Other techniques without a cooling system

If you are not blessed with a fancy cooling system, you may need to get creative with controlling the ferment. Tanks might be moved outside on a hot day, winery doors thrown open for airflow, bottles of frozen water added regularly to tanks and dry ice added as the grapes are being processed. For gentle warming, little fish tank heaters sometimes find their way into barrels.

I maintain the failure of my first ever bathtub wine in 2019 was mostly down to the downstairs flat irresponsibly turning on the heating in September. I didn’t have these ingenious tricks that people use back then and I’m sure there are many more out there I’m excited to discover, but not as excited as I am by precision.