Filtration unfiltered

Filtration is one of those quietly divisive topics in winemaking, a rarely talked about detail that sparks big debate. Many see it as essential, a final act of polishing and protection before the wine travels out into the world, especially if it is travelling around the world. Others see it as unnecessary interference, stripping character in the pursuit of aesthetics. Like my views on most things in wine, I’m somewhere in between, which is great for a decision-making outsourcer like me, but makes it extra tough for you…

What Filtration Actually Is

At its simplest, filtration is just forcing wine through something that catches solids. It’s like very fine sieve. Actually, it’s a exactly like a filter, which on reflection, is a normal word for a thing you are probably familar with. In winemaking, it is used to remove particles, yeast, and bacteria that could cause haze, refermentation, or outright spoilage after bottling.

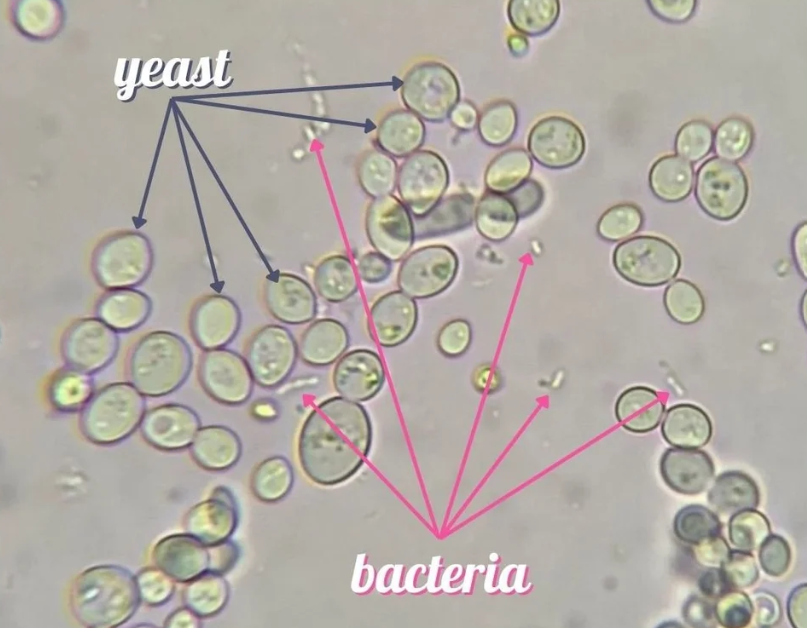

Remember these numbers, because it’ll come in handy when we look at the filtration options later: the typical size of a wine yeast is around 3–5 µm (microns, the equivalent of 0.003-0.005 mm), and most bacteria are smaller, usually 0.2–1 µm. Knowing these numbers, as well as what you want to avoid, helps you choose whether you need coarse, fine, or sterile filtration.

Filtration is the last chance a winemaker has in the cellar, it doesn’t always make the wine better in itself, but can prevent things going wrong.

stability, storage and travel

Filtration serves both practical and aesthetic purposes. A clear wine may be deemed to look professional, travels safely, and avoids surprises on opening. For wines crossing hemispheres, for example, a Fiano or Nebbiolo made in Australia and heading to Europe, the stability factor becomes critical. Apolgies to my Adelaide customers but long travel times, temperature swings, and variable storage conditions make microbial stability worth serious consideration.

But there’s a philosophical side too. Every time a wine passes through a filter, there’s a chance that not only solids but also subtle flavours and textures are removed. Many winemakers, especially those with a minimal-intervention ethos, believe that filtration can dull a wine’s energy, the feeling of it being “alive”.

On the other hand, unfiltered wines carry a small but real risk of instability. In a warm London kitchen or hot restaurant, a few surviving yeast cells could start to re-ferment in bottle. This can lead to spritz, haze, or in extreme cases, exploding bottles.

Wine is rarely consumed where it’s made. Wine can face months of container time, temperature swings across the tropics, and handling stress. Kermit Lynch talks about this in Adventures on the Wine Route, a great read, he tasted wines in barrel, imported them, and then hated them on arrival. His logic was that filtration stripped out too much of the character from the wines. His solution was temperature-controlled shipping, which solves many of the problems but is very expensive.

I also like to think about how much I have enjoyed cheap Greek taverna wine, three euros from a carafe, drunk on the beach. It’s always amazing. Take that same wine home in a suitcase, and very quickly it disappoints. Unstable wines don’t travel well. But buy a cheap likely sterile filtered Greek white wine from a supermarket, it also disappoints. You can’t win. The solution is probably being on a beach.

the options

Filtration is not a binary choice either. There’s a spectrum: none, coarse, fine, sterile. Each comes with trade-offs between clarity, stability, and flavour.

None means trusting the wine to fend for itself. The texture, aromatics, and mouthfeel remain fully intact, but it might develop sediment, haze, or worse if something survives the journey.

Coarse filtration (around 3–5 µm) removes large particles and most yeast cells while keeping bacteria largely untouched. Your wine gets a clear pour without losing its perfume or bite. Depth filtration, uses thick pads or sheets made of cellulose, perlite, or diatomaceous earth. Captures particles within the depth of the pad, not just on the surface.

Fine filtration (1–2 µm) pulls out nearly all yeast and most bacteria, polishing the wine for visual appeal and bottle stability. You preserve delicate floral and mineral notes while adding safety. Surface (or membrane) filtration uses a thin membrane with precise pore size. Acts like a true sieve — anything larger than the pore is removed.

Sterile filtration (0.45 µm) removes essentially everything that could reproduce. Great for residual sugar wines or risky shipping, but at the cost of some texture and aromatics. Overkill, perhaps, unless your lab tests show a lot of risk factors. This is typically done using a cross-flow filter too, a more modern, continuous process. Wine flows tangentially across a membrane rather than directly through it. Solids are swept away, reducing clogging and wine loss. Gentle, efficient, and great for polishing, but expensive for small scale winemaking. Our batches are usually too small to use this equipment, as the losses are more significant.

These are your levers. Knowing yeast and bacteria sizes, plus the wine’s chemistry, helps you pick the right one; coarse, fine, or sterile to balance stability and expression.

How Filtration Actually Works (and why it’s a pain)

Filtration can be a delicate art and a giant, messy pain. Replacing pads or membranes is in my top five least favourite winery jobs. It’s sticky, fiddly, and prone to wine everywhere except where it should be. That’s why racking and fining are done beforehand: they remove the big solids before they clog the filters.

Practicalities matter. Pads clog, membranes blind, and wine can foam or oxidise if you’re not careful. That’s why most winemakers don’t just dump the wine straight through a sterile membrane, they stage it: fine and rack, then through a coarse filter before sterile if needed. It’s like a relay race for particles.

Every filtration stage carries a hidden cost: wine loss.

Pads and membranes absorb liquid, and tanks and hoses always hold a little back. Typical losses range from:

1–2% for small, single-pass coarse filtration

Up to 5% for multi-stage or sterile runs

On a 650-litre barrel, that could mean losing 6–30 litres, one to four cases of wine. It’s another reason some winemakers skip filtration entirely, preferring to rack carefully, settle naturally, and trust stability testing.

Closing Thoughts

Filtration isn’t magic. It won’t make a bad wine good, but it can keep a good wine from going bad. Coarse, fine, sterile, each choice is a tiny vote for stability, clarity, and survival during shipping, balanced against flavour, texture, and aromatics.