picking a picking date

summary

During ripening, grapes undergo a series of changes that influence the type of wine made. Sugar levels rise as the vine photosynthesises. At the same time, acidity decreases through respiration and the phenolic compounds evolve; tannins soften, colour pigments (anthocyanins) develop, and flavour precursors become more expressive and complex. These compounds shift from green and bitter to more tropical and ripe.

“What to consider when choosing whether to pick early or pick late?”

Winemakers must balance these elements when deciding when to pick. Earlier harvesting preserves acidity and freshness, often resulting in lower alcohol, more tension, and brighter fruit profiles. This can be desirable for crisp whites or elegant reds. Later harvesting allows for riper flavours, fuller body, and softer tannins, but risks higher alcohol, lower acid, and a loss of vibrancy if taken too far.

Ultimately, the timing of harvest reflects your stylistic intent and the conditions of the vintage—finding that sweet spot between freshness and ripeness is part science, certainly acids and sugars can be measured but also part instinct, based on taste.

Keep reading if you want more technical info, the following is an email taken from the a decision during our first vintage in 2022 with Quinta de Soalheiro.

THE TECHNICAL INFO

The first important consideration—once a grape variety and site are chosen—is the picking date. I’ve interspersed one of our earliest Not Yet Named votes on picking dates with three key reflections that have become clearer to me over the three years since that email: practicalities, picking on taste and adjusting for acid. Otherwise, I think the principles presented for our first Alvarinho hold true in every region Not Yet Named has made wine.

The overall ripening process

This graph shows the journey of every grape, you can see the trajectory of the acids and the sugars as they walk the picking time tightrope. Too late the wine loses freshness, too early and the sugars and flavours haven’t developed enough. There’s a lot going on in this graph but focus on the acid and sugar lines, the colour of the berry changing is a crude but useful proxy for the changes in phenolics that affect colour and flavour amongst other things.

This shows the ripening of a red grape. Our Alvarinho will turn from green to yellow at verasion.

“Of the holy trinity—sugar, acid, and phenolic ripeness—there’s only one that can’t be adjusted once the grapes are in the winery: phenolic ripeness. Many winemakers therefore are prepared to wait for phenolic maturity, at the expense of potential alcohol and low acid knowing they can be adjusted up or down later if needed. In the hot countries where Not Yet Named have worked this usually means acidity adjustments. However, picking based on acidity is becoming more of a trendy thing to do in warmer climates, theoretically sacrificing phenolic maturity in favour of freshness. Customers are also preferring these fresher flavours with the new found understanding the wine will have had fewer interventions.”

Acids

Grapes are made up of three main types of acid. Tartaric acid is the most significant in terms of volume found in finished wine. It forms early in berry development and concentrations remain stable throughout ripening. Malic acid is the one to watch though as it also forms early in berry development but begins to degrade after verasion and then more rapidly during ripening.To be clear we are only talking about the volume, or technically the concentration, of the different acids in the wine here. pH is a different but hugely important measure of acidity that we will talk about in future emails.

“I’ve only heard this mentioned once, but it’s worth noting: acid additions are usually just tartaric (infrequently I’ve seen lactic or malic too). But this doesn’t replace the actual balance of acids lost during ripening. It would be fascinating (and probably quite complex) to see if anyone has ever tried to recreate the full natural acid profile of a grape. Anyone who’s made it this far and has some experience I’d love to hear it.”

Sugars

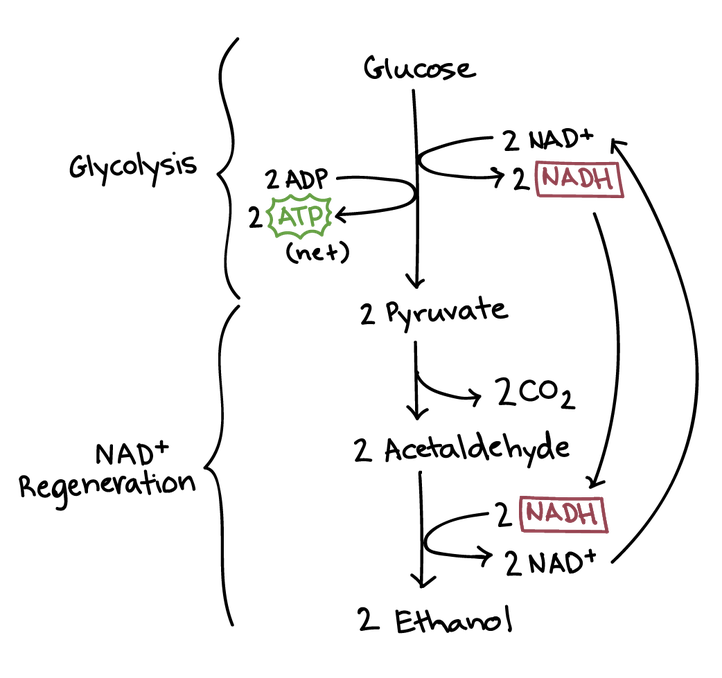

Who remembers chemistry at school? Alcoholic fermentation is the conversion of one molecule of glucose into two molecules each of ethanol and carbon dioxide. The higher the initial sugar content of the must, the more alcohol will be present in the finished wine, if allowed to ferment to dryness.

An unnecessarily complicated diagram of sugar turning into alcohol. It’s intended lend gravitas to our winemaking credentials even though we don’t understand it. Hopefully it’s in Year 2 at Plumpton.

Phenolic maturity

Phenolic ripeness (also known as physiological ripeness) refers to changes in grape phenols, compounds that include tannins, anthocyanins, flavonols and others that occur in grape skins, seeds and stems. These phenols fall into two categories: flavonoids and non-flavonoids. As the grape approaches phenolic ripeness, the flavonoid phenols – precursors of aromas, flavours, structure and colour – change from green and bitter to pleasantly astringent to soft and ripe-tasting.

There’s a double whammy here that flavour compounds are more soluble in high alcohol solutions. These aroma compounds have aromatic rings that are more hydrophobic and therefore prefer swimming in alcohol more than water.

“It’s actually quite rare that we get a vote on picking date. In reality, limited availability and the cost of pickers—along with having to schedule them a few weeks or even months in advance—make a picking date a bit of a luxury for our projects. Beyond that the winery needs to have equipment and staff ready on hand to process the grapes. Picking grapes at the perfect time only to have to leave them in a cold room whilst a press or destemmer becomes available is counterproductive.

In fact, the decision for our very first vintage only came about because two almost identical vineyard sites were scheduled to be picked on different days. So while it was presented as a picking date decision because that was the key factor in the decision, it was really a choice between vineyards, each with their picking date and winery plan already set. The rise of machine harvesting is making it easier to choose a specific date—but it comes with it’s own negative impacts on quality. If I can keep these up, a discussion for a future blog, I reckon..

The weather seriously impacts the decision too of course, this is very location and vintage dependent so here is the context of the weather in Portugal 2022 that subscribers had to consider...

”

The weather in Melgaço is almost as unpredictable as Tomasz Scafernaker’s reaction to being mildly humiliated by a BBC news reporter (see below). This has put a spanner in the works for deciding our picking date and the reality is we are more concerned with the impact of the rain than with the maturity of the grapes.

You might then ask why suggesting the 4th as a picking date when it’s the most likely day for rain. The reason is simple and that the grapes will not absorb the rain immediately, but it takes around 24 hours for them to take in the water and then another 3 days before the sun, in hot conditions, returns the grapes to their pre-shower levels. Hence, we are suggesting the 4th or the 8th, also bearing in mind the dates on which we have old vines available.

The Not Yet Named subscribers voted for an early pick this time - dodging the dodgy weather. Message below to tell me what you would have chosen. Thuis decision is easier said than done, picking grapes is almost as complicated as Peter Pauerwein picking Pinot in a pickle.