#7 serralunga vs roddi

Barolo has been dissected academically more thoroughly than any other region bar Burgundy, but what’s fortunate for us, is that we get to explore it with actual wine at the end. Gianluca has offered fruit for us from either Serralunga d’Alba or Roddi. Two sites that give Nebbiolo different characteristics.

But before you pull the trigger, let’s talk about the elephant in the tasting room: whilst stranger Not Yet Named things have happened, we’re very unlikely to make a Barolo.

Why Not Barolo?

Ultimately this blog is to get you to a conclusion - to help you decide whether to vote for Serralunga or Roddi as the location of our grapes. Serralunga is undoubtedly one of the most renowned communes in Barolo, much more so than Roddi, and so it may feel like I’m pushing you away from one specific option as I write, and to a certain extent I am to rebalance the seemingly lopsided vote, but it’s with good reasoning. You always have to remember that we are making a wine for a specific purpose and with certain restrictions. Our biggest restriction is that we need the wine to be bottled and delivered within a reasonable timeframe (Barolo requires at least 36 months’ ageing) and not cost me so much that it sends Not Yet Named under, drowned in elegance, acid, tannin, tar and roses. What a horror movie that would be.

That being said: even though we're not making Barolo, the fruit will still come from land where Barolo could legally be made.

The Lay of the Langhe

Nestled in Piemonte, northwestern Italy, the Langhe is one of those gorgeous wine regions with a panorama of rolling hills and castles dotted on top. Medieval towns like Alba, once called the “city of a hundred towers” have contributed to Barolo being known as the King of Wines, The Wine of Kings. Most of those towers are gone now (turns out they didn’t survive medieval family feuds), but three remain, casting their gaze over the modern wine world they helped shape.

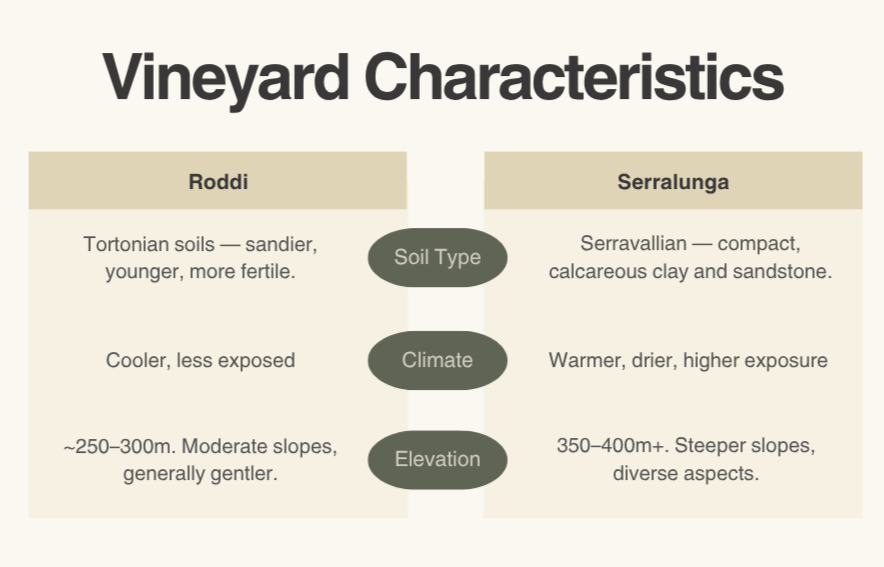

Roddi is in a northern corner of the Barolo zone, near Alba. It’s historically low-profile, but with climate change warming up its cooler sites, it’s become one to watch. Serralunga d’Alba, to the southeast, is one of Barolo’s most famous villages. Steep slopes and ancient limestone soils that create wines with elegance.

The Climate Factor

Even though Piemonte sits at the same latitude as Bordeaux its climate is significantly different. The Alps wrap around the region, creating a dry, continental microclimate. Summers get hot, followed by misty autumns and cold, foggy winters—perfect for slow-ripening Nebbiolo. But things are changing as it hots up. Climate unpredictability is also the new normal. I’ve seen Gianluca constantly checking the weather across his six sites on his phone. A situation made possible by modern day technology and necessary given the increase in the unpredictability of weather.

You’ve chosen Nebbiolo, the diva of the vineyard, high-maintenance but undeniably brilliant. It buds early, ripens late, and is vulnerable to just about every calamity nature can throw at it. Producers have planted it on the sunniest, most favoured slopes, typically south or southwest-facing, to help it ripen fully. But here’s when climate change has kicked in: the very sites that were once most prized (like Rabajà) are now too hot in some vintages, producing flabby wines that miss the mark. What used to be a surefire bet is now a risk and the emerging regions are those where ripening used to be a challenge.

Which brings us back to Serralunga and Roddi.

Serralunga d’Alba

Serralunga is Barolo royalty. It sits on the oldest soils in the region—12 million-year-old Lequio formations packed with clay, sandstone, and a whopping 28.9% calcium carbonate (the highest in the DOCG). That gives you wines that are structured, deep, mineral-rich, and built for the long haul.

This is where serious, age-worthy Barolo is born: dense, tannic, demanding patience but richly rewarding when the time is right. Yet, not every wine from Serralunga is double diva. Some show more accessible fruit and elegance on release—proof that structure and drinkability can coexist.

Roddi: The Under-truffle-dog

Roddi is lesser known, lesser written about—but not lesser loved. Sitting on Tortonian soils, particularly the blue-grey Sant’Agata Fossili marl, Roddi’s terroir produces more elegant, perfumed, and fruit-forward expressions of Nebbiolo. The wines are softer, more approachable, and don’t need as much nurtre in barrel and bottle to sing.

Favourite fact I’ve found during my research is that it’s also home to the University for Truffle Dogs. I haven’t looked into the details of this fact because I desperately want it to be true.

But what does this mean for the wine?!

I’ve taken a data-based approach to this analysis. I’ve plugged in 10 wines from each region into a well-known AI tool to pull out the most typical descriptions for each region, across the three things I look for when assessing grapes; fruit, acid and tannin. And added prestige because, it’s important…

Of course, the final style will be impacted by what we actually do with the winemaking choices but it will give us an indication of where we’re headed.

This is a classic wine conundrum: Do we chase prestige or pleasure? Go with the terroir that says Barolo heavyweight, ultimately considered the superior fruit, or side with the soil that makes wines that have historically given generosity and pleasure?